SMITHEREENS*

The Photographs of Courtney Marie Musick Harvey

The Family by Robert CreeleyFather and motherAnd SisterAnd SisterAnd SisterAnd SisterAnd SisterAnd SisterAnd SisterAnd SisterAnd SisterAnd Sister.I first noticed Courtney Marie Musick Harvey’s work on Instagram. It was a black and white photo she had taken on her phone, of a black dog with glittering eyes poking its snout at a small child rolling on the bedroom floor. It was accompanied by these words: “Someone said to me once, ‘you’re just a mom.’ So I’ll be Danae--Mnemosyne--Samuel and Frances with dust motes when we lived above a racist troglodyte on the brick streets…”

I was pleased, not only by “brick streets,” but by her reference to Danae--the maiden sealed in a room by her father, then impregnated by Zeus in an orgasm of gold pieces--whom I’d just written about for www.bookandroom.com in “Household Gods.” Courtney Harvey fixes on Danae as mother rather than prisoner. Numerous photographs over the years are of her two young sons, now aged eleven and six, their emerging features still veiled by the mystery of beginnings.

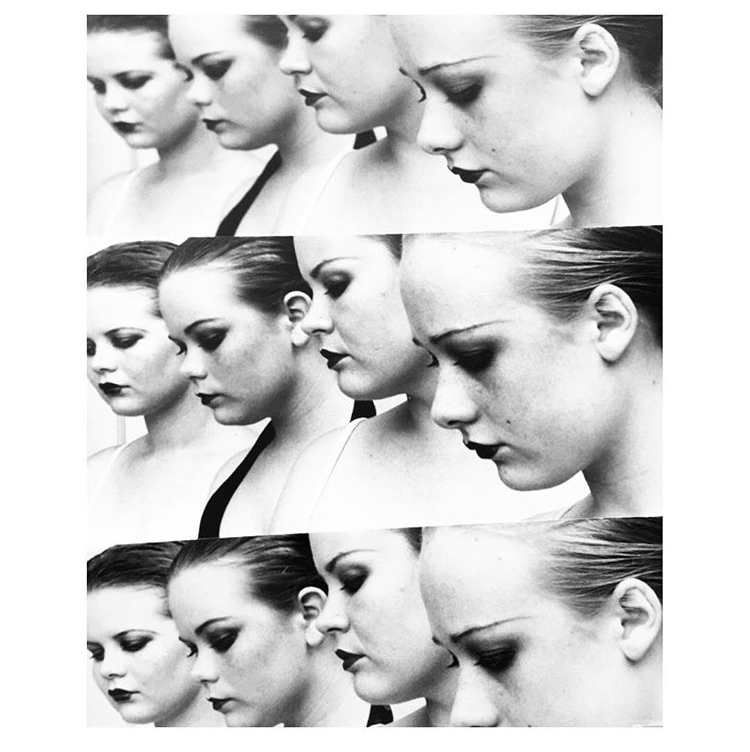

Diane Arbus once remarked, “My favorite thing is to go where I’ve never been.” That statement depends on where you’ve been already. Courtney Harvey, the third of seven sisters, was born in 1986 in Virginia, where her father’s military career and, later, both parents’ nomadism carried her family “house to house, town to town,” seventeen addresses she and her sisters can remember. Now living in East Texas and married fourteen years, she goes or stays where she knows people intimately, revealing each time a bit more of whatever was concealed at first, second, or ten-thousandth sight. Her adventures have longevity.

I have always found going to new places much less daunting than revisiting old ones, which takes more courage. For in repetition is the fantasized repair of whatever went wrong before; as well as a return to whatever once went right that we cannot let go of. Thus we retouch our troubled memories; or seal the good ones against change. Photographs apply new patinas to ancient history, including the history of photography itself.

In Courtney Harvey’s images are radiant traces of Sally Mann’s unearthly odes to childhood; faint spectres of Diane Arbus’s unrated miasmas. Harvey’s pictures are eerier than either, because they are more informal, less exquisitely framed. Their expertise is so casual it takes you by surprise; an aesthetic hidden within an unaffected family album.

Like Mann and Arbus, Courtney Harvey is a portraitist; but she is too busy to orchestrate. Nobody in her pictures sits still, nor rarely do they pose; and if so, only for a second. Her subjects are caught up in a moment of strangeness she watches with burning, passionate familiarity: ”bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh.” Courtney concentrates religiously upon her own blood; beings she was born alongside or gave birth to. Family may be a place to escape from, but kin is still where she settles.

The inherent anxiety of childhood lists on the verge of every image; a darker margin to the happiness of play: swimming, pets, plants, painting, and disguise. Fears, along with the features which mark Courtney’s parents, sisters and all their children, pass through generations, even those of tribes to whom we are not related. She remembers:

“We had read Number the Stars in class and loved it. If you could look through time to those evenings you would see two girls--one black, one white--both with white baby dolls. Our heads wrapped in pillowcases as we ran through the pastures from the pretend Nazis; saving our Jewish babies. A strange and beautiful memory for me.”

Small, scant country schools were expanded by Courtney’s learning at home with her sisters, more an amusement than a labor. The girls pieced it together themselves--in my opinion, often the best way, because it is shaped by true interest--from their father’s idiosyncratic library:

...My education was one of my own making. My father stockpiled books like a hoarder. Most of them were religious books, but there were others as well. Stacks of photograph books ranging from old Hollywood glamour to Life Magazine’s graphic war photojournalism. We also immersed ourselves in his old medical books, poetry collections, army survival guides, Greek mythology, and classical literature. I rejected school in favor of my books, old movies, and art. My institutionalized education was nothing short of abysmal. At home, however, in our odd capsule of sisterhood, I could never absorb enough knowledge.

Religion was as scattershot as books and houses:

We “church hopped.” Mostly Pentecostal, Southern Baptist, Assemblies Of God, “non-denominational” (whatever the hell that means). My favorite were the predominantly black churches. They were friendliest, more accepting, and they knew how to sing & cook the best...Now, we raise our boys to question, to seek, and to come to their own conclusions.

In creating a startling, surrealistic photographic oeuvre, Courtney Harvey simply began with what her real life looked like. She continues to connect its sometimes missing parts--her past, her sisters and parents--to being a mother, among her other earthly duties, delights, and snares.

In responsibilities begin dreams.

The photographer at fourteen.

*https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/smithereens

Although no one is entirely positive about its precise origins, scholars think that smithereens likely developed from the Irish word smidiríní, which means "little bits." That Irish word is the diminutive of smiodar, meaning "fragment." Written record of the use of smithereen dates back to 1829.