LOVE LETTERS Marcel Broodthaers: A Retrospective

What is painting? Well, it is literature. What is literature then? Well, it is painting. --Marcel Broodthaers, 1963

I dream of a new alphabet. --Marcel Broodthaers, 1974

Every week I make a ritual trip to Three Lives bookstore on West 10th Street, where I always buy one book, sometimes signed by the author; not to read, but to own. I am shoring up a small hoard of printed matter whose visual presence and physical heft, neatly shelved, sustains me while I work. The typefaces of these books, for me, are scintillating shapes brimming with personality. I wonder at the odd genius of their makers, for whom they are so often named: Didot, Cochin, Bembo, Garamond and of course, the incomparable Gill, pedophile though he was.

Marcel Broodthaers (Belgian, 1924–1976). Moules sauce blanche (Mussels with white sauce). 1967. Painted pot, mussel shells, paint, and tinted resin, 14 3/4 in. (37.5 cm) diam.; 19 1/8 in. (48.5 cm) high. Private collection, New York. © 2016 Estate of Marcel Broodthaers / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SABAM, Brussels

Two months ago I saw the “immersive”--as they say--Marcel Broodthaers (Belgian, 1924-76) retrospective at MoMA. I apologize to readers for not reviewing this wonderful revelation of an artist obscure to most Americans while it was still on exhibition. But MoMA’s vast, exquisite catalogue accompanying that show has been my delectation ever since, so I will share a bit about its contents here.

A large, lavishly illustrated book is, if anything, the best topos for Broodthaers’ singular works, which consist abundantly of printed or painted words. The 350-page catalogue, edited by Christophe Cherix and Manuel J. Borja-Villel, contains essays by such notables as philosopher-critic Benjamin Buchloh, Jean-Francois Chevrier and Thierry de Duve, among others. My favorite contributions are two essays by Cathleen Chaffee, who catches perfectly Broodthaers’ scintillating balancing act of text and image.

Marcel Broodthaers was a poet turned artist who abided, throughout his creative life, in what Marshall McLuhan called the Gutenberg Galaxy, that place where signifier and signified engulf us in the pleasures of texts. Broodthaers’ compact art career spanned only twelve years, until his death in 1976, but it is an exceptionally dense, complex, yet ordered and unified one. The four distinct periods of his subsequent work--literary exhibitions (1963-1967), an invented museum (1968-1972), paintings (1972-19) and “Decors” (1974-76)--are all suffused by the written, printed, cinematic or painted word.

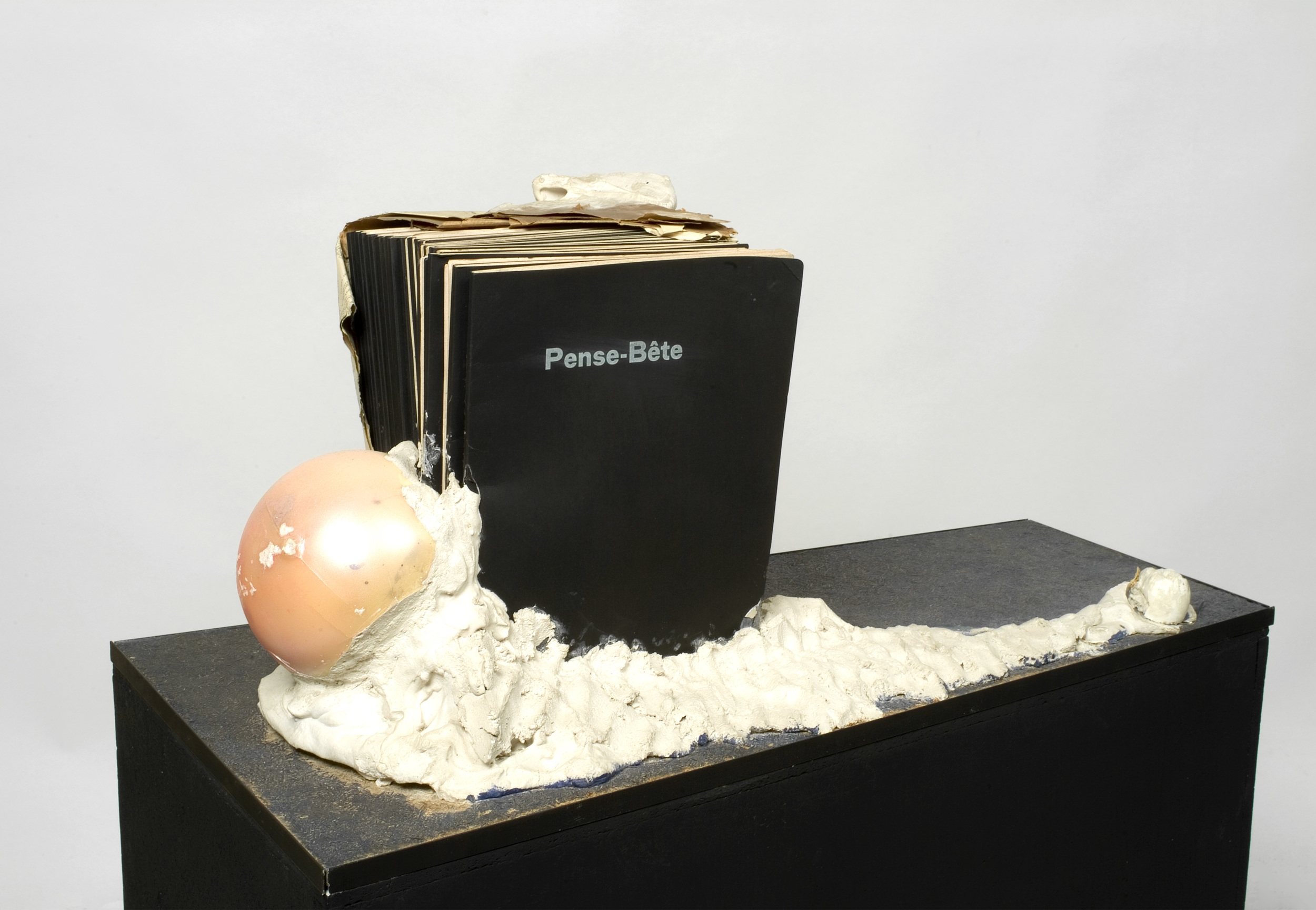

In 1963, at the age of forty, Broodthaers publicly turned to visual art because he was a commercial failure as a poet. He inaugurated this leap of irony and faith by encrusting the unsold editions of his last poetry book--entitled Pense-Bete (aid to memory)-- into a sculpture of white plaster, a first act and work as a visual artist which reified and enthroned his heretofore unnoticed writing. During this early period Broodthaers made objects, usually incorporating wordplay, from cast-off materials such as egg or mussel shells, coal or frites (fries).

Marcel Broodthaers (Belgian, 1924–1976). Pense-Bête (Memory aid). 1964. Books, paper, plaster, and plastic balls on wood base, without base: 11 13/16 × 33 1/4 × 16 15/16 in. (30 × 84.5 × 43 cm). Collection Flemish Community, long-term loan S.M.A.K. © 2016 Estate of Marcel Broodthaers / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SABAM, Brussels

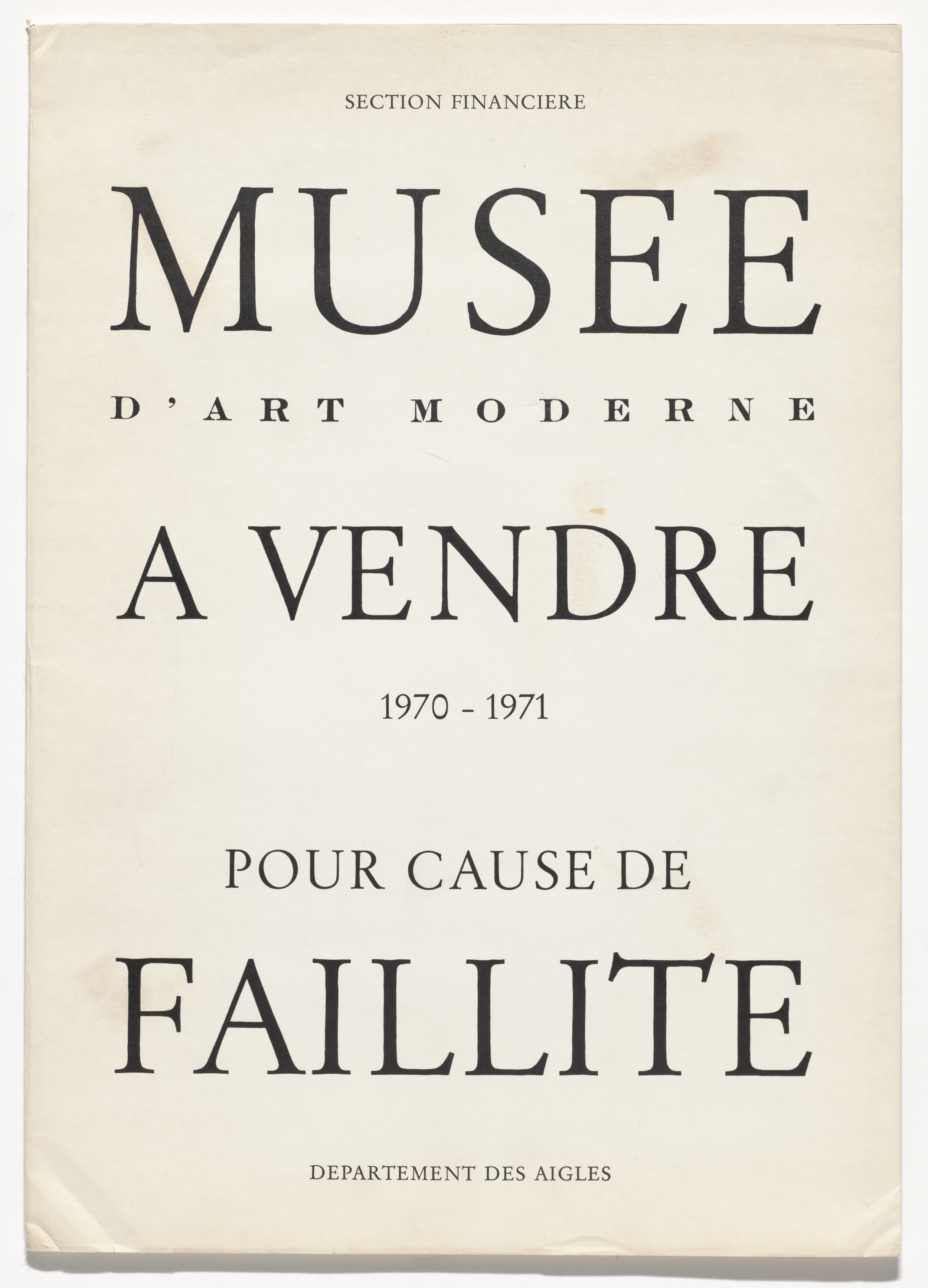

Then, in 1968, his avowed career took a curious turn. Broodthaers declared he was no longer an artist and appointed himself director of his own museum, which he called the Musee d’Art Moderne, Departement des Aigles (Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles). He began to explore the ancillary activities which surround and support a museum-- documentation, publicity and finance--creating a cascade of announcements, publications, films, slide projections and objects. For the next four years he displayed these works, as always, heavily embedded with words, in twelve temporary presentations of the Musee, which he called “sections”, in seven European cities.

Marcel Broodthaers (Belgian, 1924–1976). Musée d’Art Moderne à vendre–pour cause de faillite (Museum of Modern Art for sale–due to bankruptcy). 1970–71. Artist’s book, letterpress dust jacket wrapped around catalogue of Kӧlner Kunstmarkt ’71 (Cologne: Kӧlner Kunstmarkt, 1971), with artist’s inscriptions, overall (folded, with catalog): 17 11/16 x 12 5/8 x 5/16 in. (45 x 32 x 0.8 cm). Publisher: Galerie Michael Werner, Cologne. Edition: 19. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Partial gift of the Daled Collection and partial purchase through the generosity of Maja Oeri and Hans Bodenmann, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III, Agnes Gund, Marlene Hess and James D. Zirin, Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis, and Jerry I. Speyer and Katherine G. Farley, 2011. © 2016 Estate of Marcel Broodthaers / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SABAM, Brussels

In 1972, ever quixotic, Broodthaers announced that his tenure as Director of the Musee had ended, and that, once again, he was an artist. He began a new form of painting in which he physically painted nothing himself, but instead printed words onto canvas. These are among the most beautiful works in his repertoire. In a splendid catalogue essay, Kim Conaty pinpoints the source of their haunting presence:

“With Peintures litteraires, writers and artists [ranging from Oscar Wilde and Lewis Carroll to Edgar Allan Poe and James Joyce] are the subjects of paintings that are themselves composed only of printed text. Broodthaers’ choice of letterpress--the standard technique used to print books until the second half of the twentieth century--conflates the act of writing with that of painting. Furthermore, his aesthetic decisions regarding the works’ final appearance--which included choice of typeface, text color, and the density of printing--derive as much from the world of book production as from that of art.”

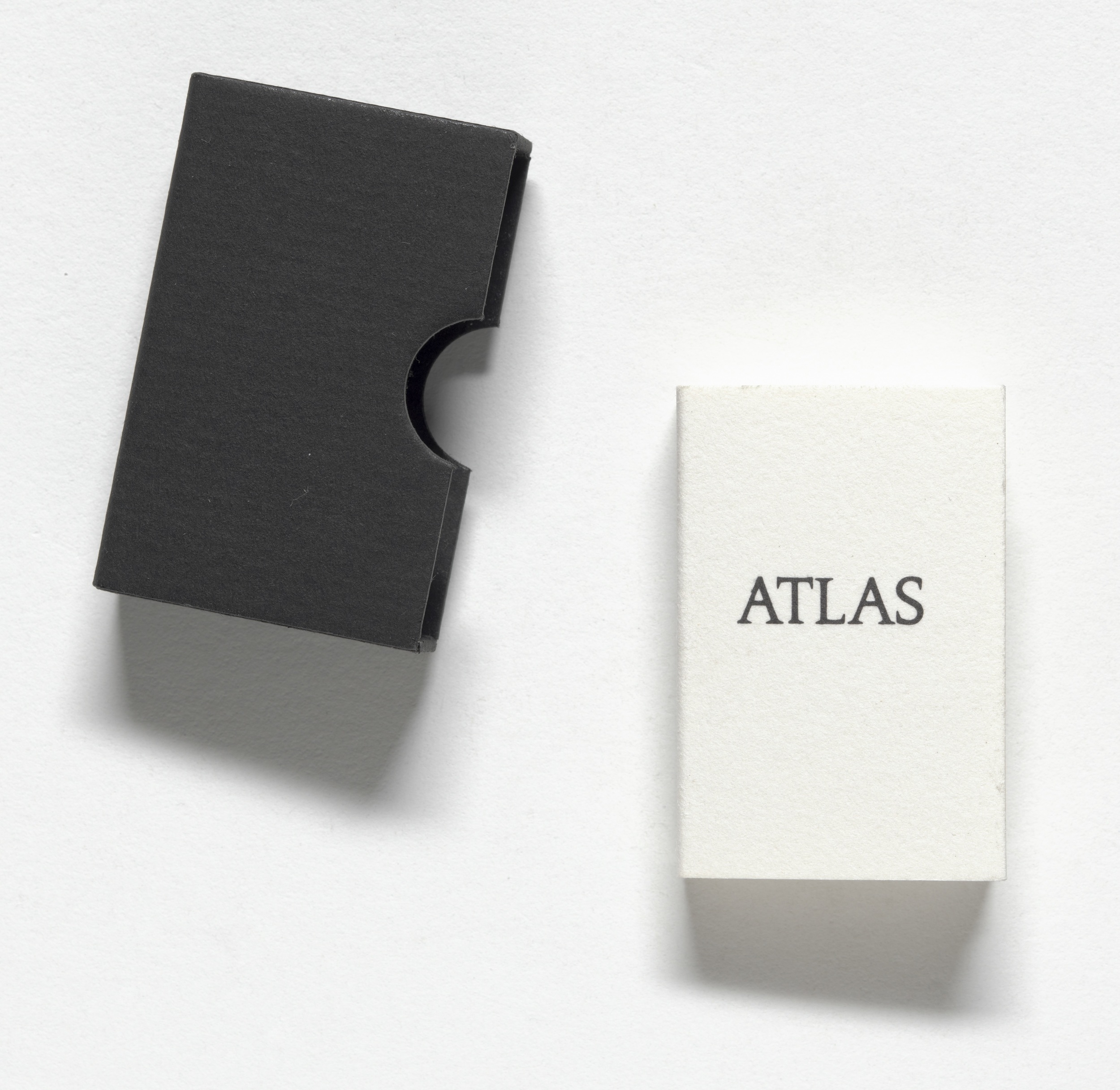

Marcel Broodthaers (Belgian, 1924–1976). La Conquête de l’espace, Atlas à l’usage des artistes et des militaires (The conquest of space, atlas for the use of artists and the military). 1975. Artist’s book, offset lithograph, thirty-eight pages, with slipcase, closed: 1 5/8 x 1 1/8 x 3/8 in. (4.2 x 2.9 x 1 cm). Publisher: Lebeer Hossmann, Brussels. Edition: 50. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Partial gift of the Daled Collection and partial purchase through the generosity of Maja Oeri and Hans Bodenmann, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III, Agnes Gund, Marlene Hess and James D. Zirin, Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis, and Jerry I. Speyer and Katherine G. Farley, 2011. © 2016 Estate of Marcel Broodthaers / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SABAM, Brussels

From 1974 until his death in 1976, Broodthaers organized large-scale displays which he called Decors, exhibiting examples of his past work along with new works and borrowed objects. He surrounded these works with elegant atavisms redolent of 19th century Great Exhibitions: potted palms, carpets, mahogany vitrines, flying in the face of the modern white box as locus for display of art. In French, the word decor also suggests a film set, and Broodthaers shot a number of films in his exhibitions.

Installation view of Marcel Broodthaers: A Retrospective. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, February 14–May 15, 2016. © 2016 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck

A final, personal comment provoked by this beautiful book: I doubt many people, even art and book lovers, share my thin skin when it comes to typefaces. An ugly one passes as unimportant; a beautiful one never receives the admiration it deserves. Typography, I suppose, is considered a minor art, and yet it is the one which unites and exalts the great arts of writing and drawing. Marcel Broodthaers--the retrospective, the catalogue, and, of course, the artist himself--is, for the lover of letters, a galaxy of pure pleasure.