ON THE INSIDE

At a moment when American liberty and justice for all seems eerily suspended,, activist-curator Tatiana von Furstenberg has gathered 220 drawings by incarcerated LGBTQ artists into a startlingly beautiful and moving exhibition, ON THE INSIDE, at the Abrons Center until December 18th. It is impossible to wrest these drawings from the terrible context in which they were made, and yet many transcend their social and political significance, becoming simply works of art, worthy of a long look, and thoughtful interpretation.

Representation of many kinds, from writing to drawing, would seem to me to be grounded in three things: observation, skill, and longing.

In an essay on writing to appear on New Year’s Eve 2017, on bookandroom.com, I have written, “The [writer’s needs] are, in reality, quite slender: materially speaking, unlike other arts, writing comes cheap.” After seeing, ON THE INSIDE, I’ve had to revise this opinion, realizing that visual artists, too, may achieve great things with the most minimal ways and means, and in the most constrained of circumstances. At the same time, the price paid by bodies, minds and souls to bring these works into being is as high as any could be: the loss of liberty and autonomy, the coercion from the individual of identity and dignity.

Ruben T., Spread Your Wings

ON THE INSIDE reminds us of the primacy, authority and originality of the individual hand and eye. Its currently incarcerated artists work with “basic materials the prisoners have access to behind bars: mostly letter-sized paper, dull pencils, ball-point pen ink tubes (the hard shell is deemed too dangerous), and unlikely innovations such as using an asthma inhaler with Kool-aid to create an air brushed painting.” I saw a faint tri-fold in the paper of many of these now framed works, necessary for mailing the drawing to a recipient on the outside.

I wondered who these artists are, their lives, their loves. Individual crimes and convictions were not part of the curators’ labels or my consciousness while I was looking at the drawings, but I came away from ON THE INSIDE with the near-certainty that, if not all inmates are political prisoners, they are all, to varying degrees, prisoners of politics. For-profit prisons, a 21st century reincarnation of slavery; linens, food and security services generating big business interests; the criminalization of nonviolent, often victimless offenses imposed with wild disproportion upon citizens of color; laws in 34 states barring voting by ex-felons, a population which includes about 20 million people in the U.S. overall.

There is a rich lineage in literary history of imprisoned writers: Voltaire, Cervantes, Defoe, Dostoevsky, Wilde, Kafka, Genet, Himes, Goines, Mandela, Malcolm X. The writer’s solitary work is often envisioned as taking place in privation akin to that of a cell; whereas the artist’s studio is imagined as a place of light, color, and conviviality.We think of Montmartre and Arles, not the Bastille, Reading Gaol, or Rikers. Prison might be seen as perversely ideal for writing, provided the prisoner is permitted to have paper and pencil, but it does not lend itself to the materials and practices of visual art. Visual artists who produced work while imprisoned are few; only Egon Schiele comes to mind. The Austrian artist painted several watercolors during his 24-day imprisonment in April 1912 for seduction of an underage girl, abduction, and exhibition of pornographic material to minors.

Melvin C., Martin Luther King

Using the materials and-- models-- at hand, the artists of ON THE INSIDE deal almost exclusively with one subject, the human face and human body. (Bodies in prison are plentiful.) If there is drawing from live models here, there is also clearly, in the case of celebrity portraits, the use of photographs from magazines as inspiration. There is the loving verisimilitude of Melvin C’s portrait of Martin Luther King; the elegant graphic power of Jeffrey B’s Obama and Friends.

I mentioned longing as an element of art-making. The several hundred images in this show emanate desire beautifully and plangently, transmitting to us the tragedy of prison, which so clearly is the woe of separation from one’s own life, one’s own loves.

At the same time as we see separation, we are aware in these works of the strange, imposed proximity in prison of others, a forced intimacy among inmates which, at its best, creates fellowship, and bedfellows. There was erected in the middle of the gallery a sort of cabin, filled with graphic sex images, with a sign at the entrance warning that children under thirteen could enter only if accompanied by a parent. I did not find the images within much more salacious than the writhing, almost always erotic figures in the main exhibition. There was a lovely labia, drawn with tenderness softly in pencil; another, of a man masturbating on a toilet. Indeed, I would say softness suffuses even the most hardcore of these subjects. There is the dull pencil, endlessly tracing with feathery strokes the lineaments of desire. Eros appears to be a constant companion in confinement.

Stevie S., Acceptance

Possibly my favorite drawing in the show is Stevie S’s Acceptance, two sinuous figures in an embrace evoking altered states, against the background of a cinderblock bathroom. Their bodies are lavishly tattooed with past loves and losses, now forgotten in the unearthly, transitory miracle of fulfilled desire, as quick as it is ecstatic. “Familiar acts are beautiful through love,” is written in cursive in the drawing’s right-hand lower corner, a truth about passion that is often painful to remember.

Bruce B., Sparrow

Other images are about aloneness in captivity and the emergence from it. Bruce B’s Sparrow shows a fiercely beautiful woman kneeling in profile, downcast, her arms tattooed with Native American-inspired patterns, her face with ciphers resembling war paint, a picture of a regal figure in sorrow. Tiffany W draws a similarly defiant yet melancholy caged woman, Shawn Dee, her wings folded at her sides as she glowers out at us from behind bars. In Spread Your Wings, by Ruben T, a woman with windblown hair is lifted and liberated by a vast pair of wings.

The works I’ve described above, with their stylized depiction of people whose physical beauties are exalted to the point of exaggeration, reminded me of the sure, swooping lines of Antonio Lopez’s fashion drawings from the 1970s and ‘80s, so wonderfully exhibited at the Museo del Barrio last June. I also heard murmurs about Tom of Finland throughout the gallery.

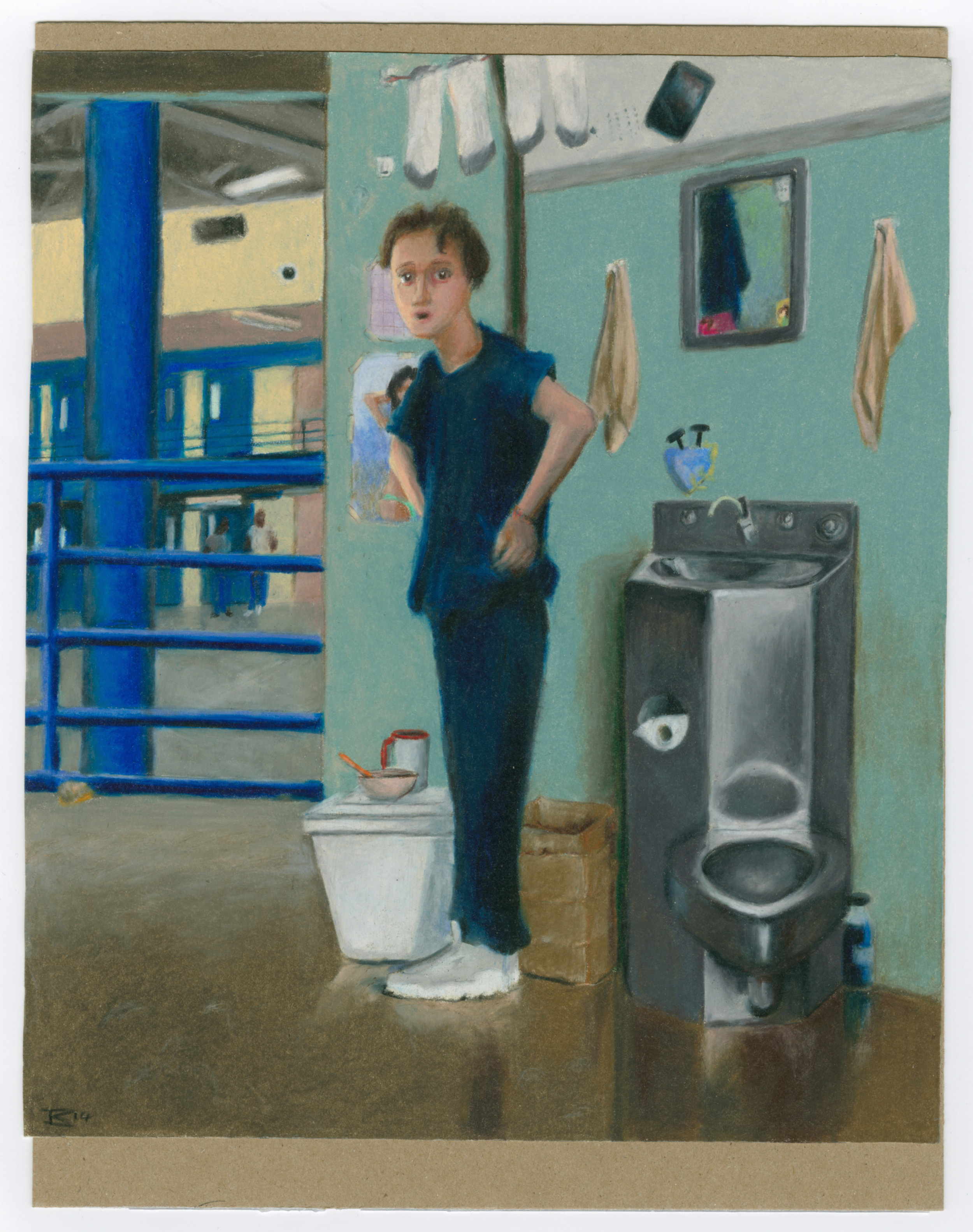

Tony B., Prison Is Worse for Some

Two quite different images also caught my eye, pictures which seemed to encompass the themes touched upon above, of isolation and connection, abjection and celebration. Prison Is Worse for Some by Tony B is the only image in full color in the exhibition. Against a green wall stands a frail figure, face frozen in apprehension, next to a steel sink and toilet with socks drying on a pipe above, towels and a steel mirror hanging on the wall, a cyan blue steel railing in the background. It is a view of the secret domestic life of prison, the washing up and making do.

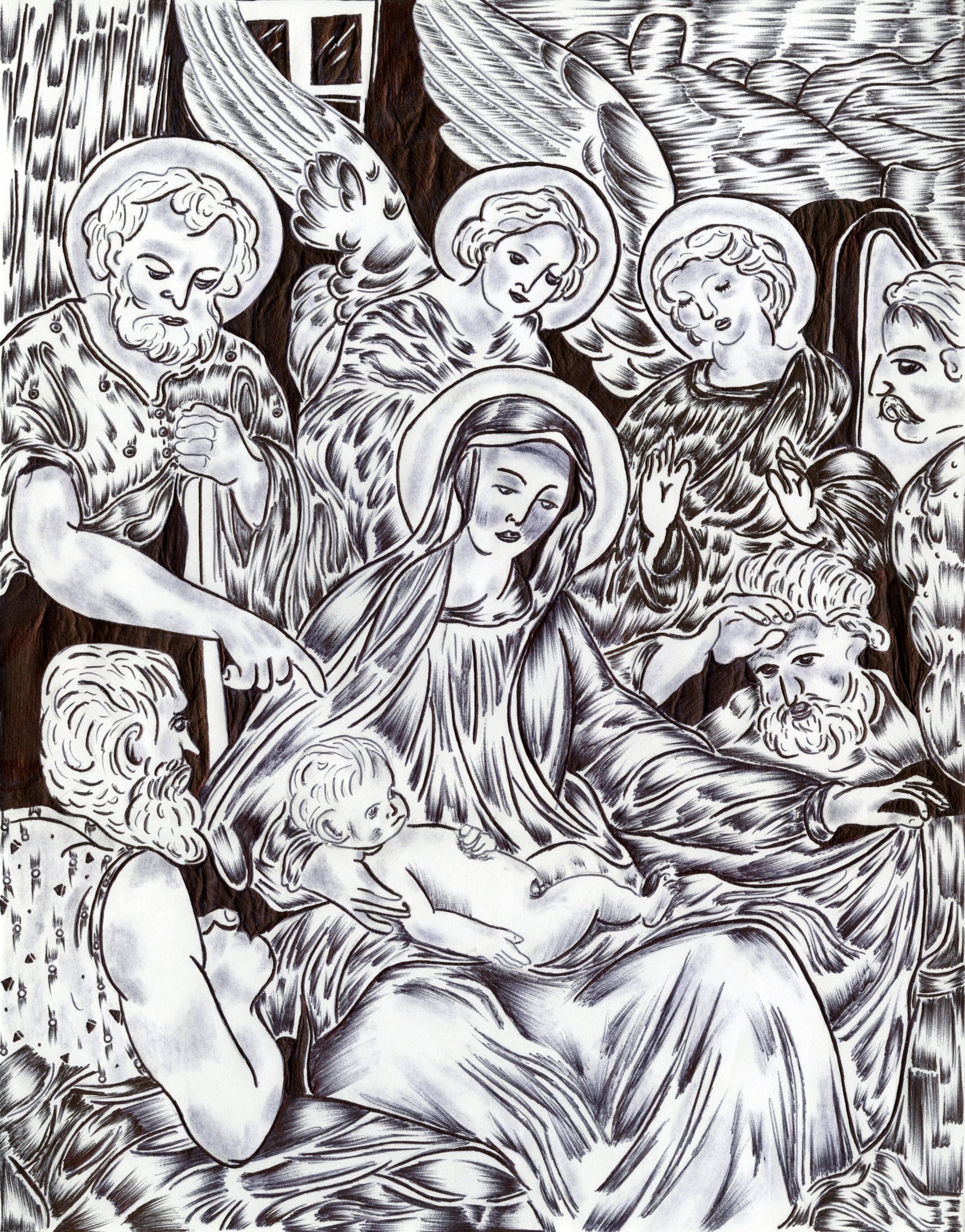

Kris H., Gift of Life

In Gift of Life by Kris H, the Holy Family is surrounded by angels and shepherds, drawn with flourishes that seem, on a formal level, to connect them, or rather to reveal the mystical connections of the scene. The flowing clothing of the figures shimmers. The intensity of this inaugural Christian scene reminded me of the charged, sensuous treatments of the subject by British 1930s engraver and typographer Eric Gill.

The Abrons gallery itself, composed of yellowish cinderblock, made a fitting setting for ON THE INSIDE. Sentences, proclamations, and fragments of autobiography by various prisoners were printed on the walls in black, providing a subtext for the drawings, and reminding us of the kinship between writing and drawing. Within the drawings themselves, too, words are often woven in, in a calligraphic cri de coeur, the hand and heart needing to inscribe and explain, even when the image says it all.

There is, in these drawings, sometimes, an ecstasy that soars, assuaging and transforming the pain of absence.