Elegy for My Apartment

The longest relationship I have had was not with man, woman, or even cat, much as I might wish for this last liaison to have been permanent. No, it was with a studio apartment, in a brownstone on 84th Street off Riverside Drive.

There I lived from 1978 when I was 21 until our final breakup in 2005, aged 48, after twenty-seven years spent arranging and rearranging assorted contents in a space measuring 21 feet by 15. There were numerous long pauses in my residency here; I often sought to escape, not so much Manhattan as from the seeming impossibility of finding a larger apartment here, and so, from time to time, I took off for Hollywood, Echo Park, London, Glasgow and Cologne, each time subletting this precious, rent-stabilized space to my neighbors upstairs or to grimy itinerant students, while I lived in adopted, impractical, impermanent splendor elsewhere.

I thought of this apartment, this room, not so much as an apartment as a fate, a solitary one at that. Downstairs lived a lady I thought of as old, a kind of independent lay religious, who seemed not to age as I did. She had no visitors. I had many; none stayed.

But whatever this apartment symbolized to me—I think of the old English ballad, “One is one is all alone and evermore shall be so”—decorate it I did, ever optimistic, time after time, just as I took on one lover after another, an enchainement in more ways than one: series, chain, repetition.

As funds increased and fluctuated throughout my life and peripatetic careers, there were improbably ambitious and esoteric schemes implanted in this tiny space, but it is the first, most modest, yet emotionally charged redecoration I wish to document here, for it was attended and orchestrated by Daniel Sachs, a great friend I knew from Berkeley, California since the age of seventeen, now, with his partner, architect Kevin Lindores, one of New York’s premier decorators; together they won the 2011 Palladio Award for Traditional Architecture.

I said back then, and I say it still, nobody has better taste than Daniel. At that time, he studied sculpture at the Cooper Union under the austere aegis of the German Conceptual artist, Hans Haacke. Daniel was able to take a break from Haacke’s stern anti-material regime by making a chair, of cobalt blue-painted tubular steel and wood, with gray velvet seat and back cushions, for a disapproving architecture professor. Daniel might have become an artist rather than designer if art education at the time had favored making; a natural-born maker Daniel was and is, and, it must be said, a consummate shopper.

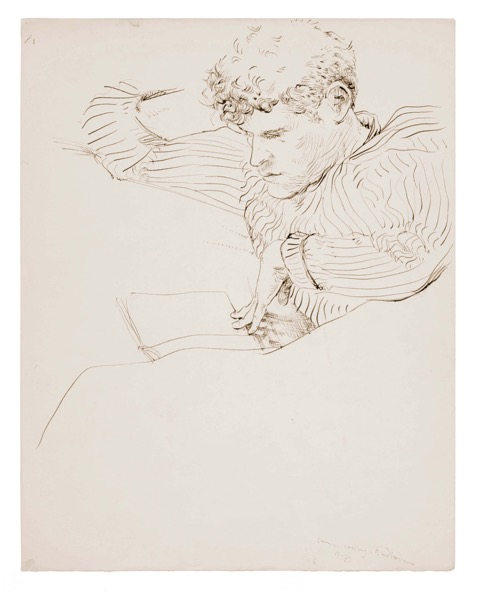

Daniel, drawn by Stephen Barker

The year was 1980. We were students, Daniel at Cooper, I at Barnard, and we were poor, pinched for time by our studies, for money by our parents. Still, we decorated. I recall an Easter vacation in which I was supposed to be finishing my senior thesis, entitled “Human Furniture: Collectors and their Objects in the Novels of Henry James.” Instead, we shopped, painted and arranged, not The Spoils of Poynton, but the spoils of several Manhattan establishments, notably Fiorucci, Design Research/Marimekko (I had bought $30.00 sheets—in dark blue and white checks with scalloped edges--in 1979 from the former; a white Formica work table for $75.00 at the latter), Henri Bendel’s house wares department (from which I bought a brown and blue striped blanket by Jean-Charles de Castelbajac) and Lord & Taylor, where my mother permitted me to use her charge account; there I bought two large finely woven Chinese baskets with lids and a white-on-white embroidered Indian bedspread. (My bed itself came from the street.) There were items I acquired from a wonderful junk store then on 110th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, a small chair, with rounded wooden organic arms and leather seat I still own, albeit stashed in a basement in Cologne; and a white craqueleur lamp, now lost, which received a variety of shades over its tenure.

I would have been content with simply painting over the pale pink walls, relic of an earlier scheme, but Daniel became enmeshed in stripping decades of plaster, paper and paint off the walls, devoting precious time to preparation, to sanding and spackling. I was alarmed at how much time this took; I was feeling guilty about my thesis, because somehow I could and would not work on this thirty page tome-to-be until the apartment was completely beautified. Writing at that juncture in my life was an exercise in pulling teeth, my own, slowly.

We purchased two gallons of paint from then S. Wolf’s Sons on Ninth Avenue and 52nd Street, in a shade of honeysuckle yellow called ‘Belladonna’. I think the brand was Benjamin Moore, but in any case, Daniel knew that Wolf’s was the place to go. He knew all the places to go and I trusted his pronouncements with adoration. For all I know, not possessing cab fare, we marched these cans the thirty blocks uptown, I in a pair of sea-green snakeskin heels from Charles Jourdan and a red shirtdress from Henri Bendel, although that was a summer outfit. Perhaps, if it was still cold I wore a brown and white herringbone tweed coat, single breasted, by Calvin Klein, along with vanilla colored boots stained with salt. To quote Joan Didion in her essay, “Goodbye to All That,” “Was anybody ever so young?” I remember the fashion and furniture items I culled so carefully then from the current fashionable emporia, paring them out of allowance and part-time earnings, with a kind of reverence. They read to me like a 1970s catalogue of style on slender means.

I possessed a few works of art: a large poster, in magenta and cobalt blue, I had acquired while on a language course in Munich, of Fassbinder’s film of the Nabokov novel Despair, entitled “Eine Reise ins Licht,” A Journey into the Light. A great friend of Daniel’s and mine, the photographer Stephen Barker, gave me a number of Hockneyesque line drawings of ourselves and other friends which adorned the yellow walls. The photographer David Armstrong gave me several black and white photographs of Daniel and other young people from the East Village, somberly glittering indicia of a glamorous gutter life beyond the anti-stylish Upper West Side, so inhospitable to me and my ilk. I also had a Chinese portrait, in red and green, of a sage on silk, borrowed from a Columbia University friend, Madeleine Hurd, who in fact lent me a number of antiques in an endowment which lasted several years, until, rightly, she reclaimed what we called “the sacred trust.” These included a marvelous carved swan daybed, a green enameled card table, and a kilim carpet, green with lozenges of orange and black, which was my (temporary) pride and joy.

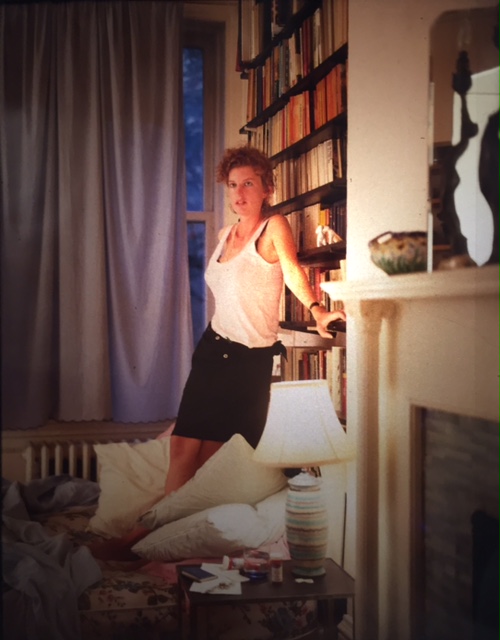

An excerpted page from the Nest magazine article, Hello To All That, which featured my apartment and text, with photographs by Adam Bartos and David Armstrong.

My studio had the appearance of a square, which was its beauty, along with a high ceiling; more awkward was the fact that it had only two windows, in the back, northeast corner, overlooking and overshadowed by the back windows of a larger building so that there was little of the natural light I craved. Then there was the kitchen, a mere alcove stuffed with front facing stove, sink and fridge. But the floor was parquet; the bathroom beautifully tiled, with an ancient porcelain pedestal sink and a leaded glass window.

I abandoned 84th Street, permanently and willingly, a decade ago, fearing if I stayed I would grow old alone, like the lady downstairs.

Now I dream constantly of that difficult space, having outlived decisively my dread of “One is one,” only too willing, now, to be alone, if I could but find the space and solitude to be so. My life and quarters are more crowded, and writing is no longer according to Flaubert’s scheme of a sentence per day.

Two dicta cover my case: above all, “Never give up your first apartment.” And, as St. Theresa and Truman Capote famously said, “More tears are shed over answered prayers than unanswered ones.” I sometimes mourn my so often unloved apartment, glad I was liberated from it, incredulous that I am no longer there. I am suffused, every day, with its memory.